Moving Hydrologic Prediction Forward — A software integration meeting at the Alabama Water Institute

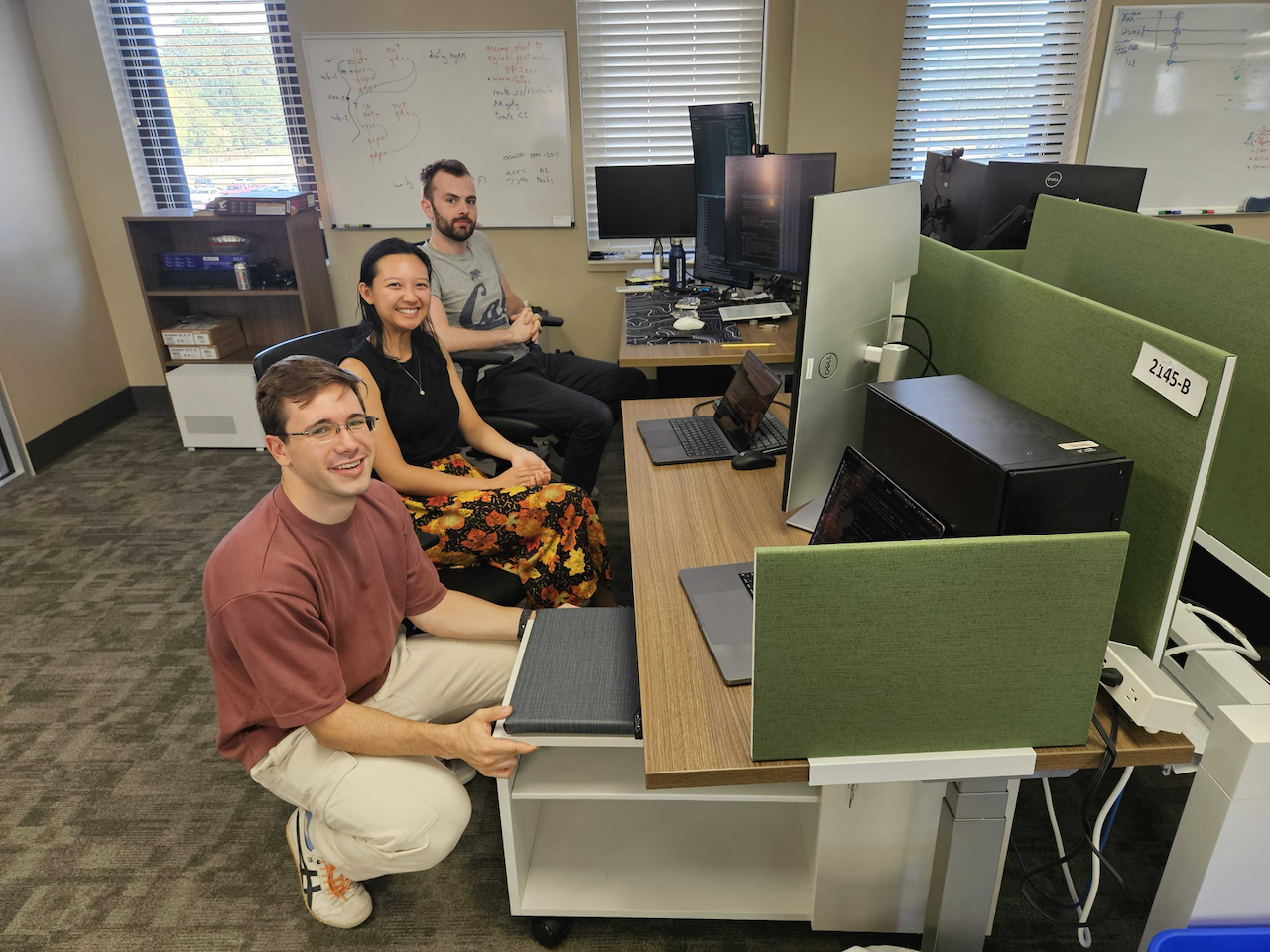

Last week, at the invitation and expert coordination of James Halgren, teams from RTI International (Sam Lamont and Matt Denno) and the University of Calgary (Darri Eythorsson, Cyril Thebault, and Martyn Clark) met at AWI for an intensive working session focused on weaving recent CIROH research into AWI’s fork of the NOAA Office of Water Prediction (OWP) Next Generation Water Resources Modeling Framework (nicknamed “NextGen”). James took the lead in developing the agenda, lining up the right scientific and technical expertise and ensuring that the week targeted the most critical software integration challenges. Throughout the visit, the RTI and UCalgary teams collaborated closely with AWI software engineers Quinn Lee, Josh Cunningham, hydrologic scientist Sifan A. Koriche, and James himself. The days were filled with whiteboards, deep technical conversations, and strategic planning around the future of NextGen water prediction. This recap captures the key themes and the momentum that carried through the week.